The cost of health care in the United States has been the source of debate for years. Questions range from the extent of Medicare and a Medicaid coverage, how—or if—the government should regulate drug prices, who deserves coverage, and how Institutions collect payments from insurance companies. But often, one important aspect is missing from the numerous conversations on health care, treatments, and financial reimbursements: the patients.

The financial burden of care, especially for cancer, is slowly becoming more recognized among providers, institutions, and policymakers. Yet, no one knows that reality more immediately than patients suffering financial toxicity and nurses who care for them. The high costs of cancer care, even for patients with health insurance, can lead to poorer outcomes for patients, decrease quality of life, heighten stress, and, in some cases, increase mortality rates.

Defining Financial Toxicity in Patients With Cancer

To begin the discussion on financial toxicity, providers need to have an understanding of what’s really happening with patients who can’t afford their treatments. It’s not just the financial impacts of care, but the ripple effect that financial hardship has on patients as they move through diagnosis and treatment and into survivorship.

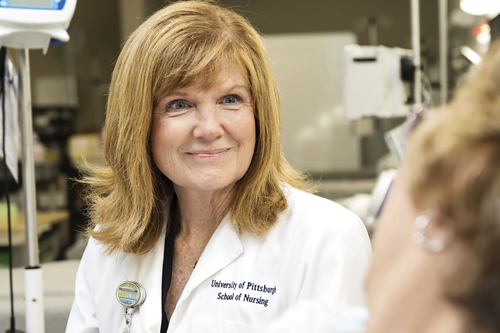

ONS member Margaret Rosenzweig, PhD, CRNP-C, AOCNP®, FAAN, professor and vice chair of research in the Department of Acute and Tertiary Care at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, said that the terms have changed over the years to provide better understanding.

“Historically, the terms financial toxicity and financial distress were used interchangeably when describing financial burden,” Rosenzweig notes. “We have started to use the term financial toxicity, because clinicians think about the outcomes of cancer in terms of toxicities and those outcomes make sense. Cancer and its associated treatments cause physical side effects, emotional side effects, and financial side effects. Once we think about financial toxicity in those terms, we can begin to do better assessments and hopefully, provide some interventions to help.”

ONS member Judy Koutlas, RN, MS, OCN®, manager of cancer care navigation at Vidant Medical Center in Greenville, NC, said that patients’ struggle with financial toxicities can increase as time goes on.

“Financial toxicity becomes more of a chronic issue across the entire continuum of care. Acute exacerbations may occur along the continuum, such as disease recurrence or progression, a spouse or family member developing significant illness, comorbidity flare ups, or a loss of employment or insurance,” Koutlas notes. “Barriers exist for patients to afford gas, food, housing, transportation, and basic family expenses. Over time, these chronic issues may lead to an inability to pay monthly household bills, resulting in bill collectors or the patient eventually filing for bankruptcy.”

Rosenzweig has looked closely at the data provided by national agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and seen the prevalence of financial effects on patients with cancer.

“The CDC says that the burden of illness is higher for patients with cancer than for other patients,” Rosenzweig says. “It reports that 13% of nonelderly patients with cancer spend at least 20% of their income on out-of-pocket expenses, and 50% percent of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer pay at least 10% of their income for cancer treatment and related out-of-pocket costs.”

Financial Toxicity’s Effects on Cancer Care

In fact, Rosenzweig and her colleagues saw patients struggling with the cost of copays, parking, travel expenses, housing costs, and more at their own institution.

“In a survey of women with metastatic breast cancer that we conducted in our own cancer care setting, we found out that women were visiting the clinic 1.5 times and spending an average of $71.47 for each visit, including copay, parking, and traveling costs,” Rosenzweig notes.

A total of 43.5% of Rosenzweig’s sample audience reported that they experienced moderate or extreme cancer-related distress.

“Although cancer-related distress can be for a multitude of reasons, we found that—regardless of income—a little more than half of the patients specifically attributed their distress to costs of care,” Rosenzweig says. “That’s pretty remarkable when you realize that these patients have stage IV breast cancer. You might think the distress would be from their serious illness or toxic therapies, but it’s from financial worry. We really need to do better.”

Koutlas adds that in many cases, patients take it on themselves to remedy the situation—often with unintended consequences.

“There are costly oral medications with high copays and out-of-pocket expenses. In those cases, patients may decrease compliance. They may take fewer pills per day than recommended so the prescription lasts longer. They may even stop therapy early or refuse to continue therapies because of high costs,” Koutlas says. “Patients will often say, ‘I don’t want to put my family in a place where, if I die, there’s this huge amount of debt.’ Financial distress often leads to anxiety, worry, and depression with increased symptoms. It doesn’t just decrease quality of life, it potentially decreases survival.”

Helping Patients Ease the Financial Burden

Having financial discussions with patients is never easy. Yet, oncology nurses are in a unique position that allows them to recognize a patient’s daily experience. Building discussions from there can go a long way to advocating for change and easing the financial burden.

“The awareness of the financial toxicity that women with metastatic breast cancer were experiencing in our clinic came from the nurses. They asked for some guidance in documenting the issue,” Rosenzweig says. “Once we established the toxicity, our administration obtained a grant to assist with patient parking costs. I think this can be a template for nurses in cancer care. Documenting a problem with patient evidence can be powerful, because then the problem isn’t something read about in literature—it’s documented among your own patient population.”

Koutlas says that other oncology nurses can take similar steps. “Be there to advocate for your patients,” she says. “Get them timely access to assistance programs, connect them with social workers, and be sure to listen closely as they describe their own situation. Sometimes, you have to think outside of the box for a solution. If you can, link them to local resources that might provide free transportation for office visits, help with utility bills, or anything else in your community. Most of all, you can empower them to take action themselves.”

Preventing Financial Toxicity for the Future

According to Koutlas, transparency is key to limiting future financial distress in patients with cancer. “We need to find a way to be more transparent about the true costs of cancer care,” she says. “As new therapies—in particular oral medications and immunotherapy—are developed and used effectively, we need to discuss with patients and their families the costs of these treatments in terms of benefit versus risks. We need to be up front about the cost, and it should be incorporated into the goals of care discussion.”

“We know that not every patient experiences financial burdens, but a simple screening tool tailored to your community and patients’ known financial stress scores could be used on admission,” Rosenzweig says. “Patients with the possibility of financial distress could then be referred to a financial counselor or social worker before actual distress occurs.”

Rosenzweig and Koutlas both note that although referrals to social workers and financial counselors are a positive step in the right direction, resources to help patients ease their financial burden are still limited. Navigating patients and their families to local and national assistance programs is crucial to finding financial support.

“Ultimately, nurses must continue to be strong advocates,” Rosenzweig says. “They need to push for affordable health care, fair drug prices, and community resources that can be made available to vulnerable patients during potentially life-ending illnesses.”