Building relationships with patients is just one of the many roles of oncology nurses. However, it’s generally not possible to see your patients every day. This isn’t uncommon, but it can pose problems to oncology professionals treating patients with head and neck cancers.

ONS member John Hillson, RN, OCN®, radiation oncology nurse at the Duke Cancer Center in Durham, NC, saw patients coming in concerned about tumor changes. The ability to track these changes were difficult, especially in patients with whom he was less familiar.

Identifying the Problem

“I was a new nurse to radiation oncology, and I had a patient I was unfamiliar with tell me that he thought a new tumor was growing despite treatment. I had only met the man once before,” Hillson remembers. “His attending physician was at a conference. I felt there had to be a better way to keep track of tumor growth. Some of the tumors were mutilating, invasive, and rapidly changing after surgery or during interventions such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy. These changes in appearance were often difficult to describe in the detail that’s warranted.”

As Hillson said, a better way was needed. He looked to his colleagues working in dermatology and wound care and saw their use of photography to measure progress and change in their patients. He wanted to use photographs in a similar way, but he didn’t want to bloat their hardcopy medical records to unmanageable sizes. Thankfully, technology helped usher in change.

“Cameras were already used in radiation oncology to verify the setup, and we’d take a photo of each patient’s face for identification prior to initiating radiation treatment,” Hillson says. “But when we went to an electronic medical record (EMR) five years ago, I thought this was an opportunity to have those photos of the tumors accessible across a patient’s entire trajectory of care—both inpatient and outpatient.”

Implementing the Solution

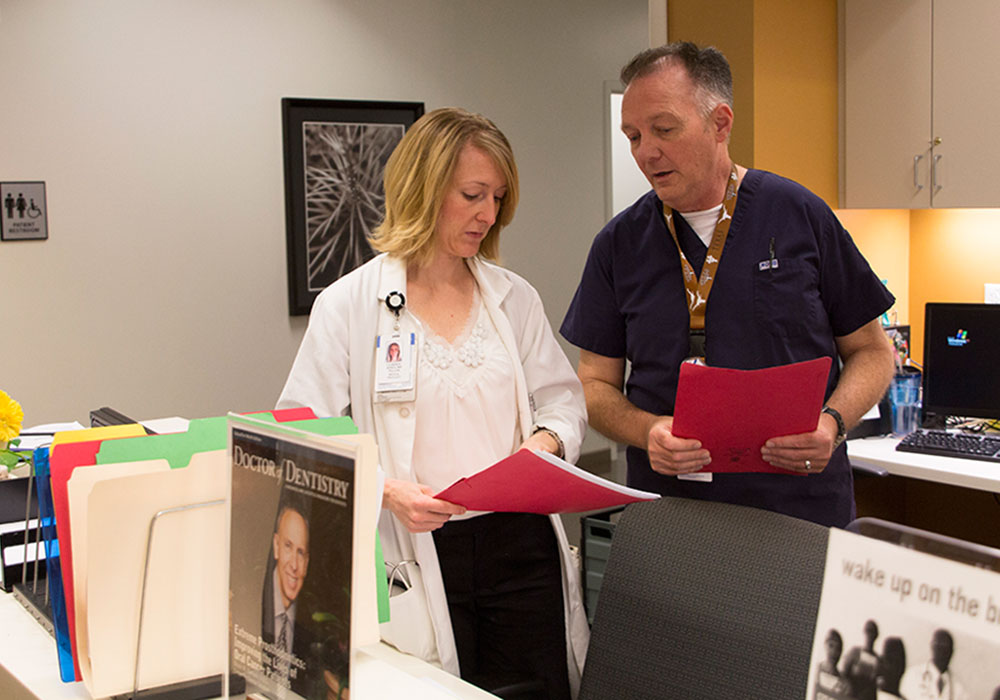

Hillson has incorporated photographs into every weekly treatment visit, along with follow-up visits. At weekly treatment checks, Hillson measures visible changes over time by placing anatomic landmarks near the tumors for reference. He also uses a measuring tape within the visible field to mark the size and change in growths. Hillson recommends taking multiple shots of affected areas from different angles.

“When photographing someone’s scalp, I learned to take photos of the scalp from anterior, posterior, left and right. This was particularly helpful for more aggressive disease or worsening side effects, as I could have something appear outside of the camera’s visual field,” Hillson says. “For noses, I now take three images—left, right, and straight on. For a neck, I take photos face on and from the affected side.”

Beyond the advantages for nursing practice, Hillson notes that other members of the interprofessional care team are able to use the photos as well.

“Sometimes the attending physician is at a satellite facility. Once the pictures were put in the EMR, he was able to see the images immediately and respond appropriately to impact care in a positive and timely fashion,” Hillson notes. “With one patient, I could see with serial images that a mass was a half centimeter bigger in 48 hours, despite radiation therapy. The treatment was revised to respond to the changes in size.”

According to Hillson, care coordination across disciplines improved by using photographs as well. The wound care team can see the same photographs as the oncology team. If the wound is changing or getting worse, those providers can revise care plans to adapt to those changes.

Adopting in Other Practices

Hillson encourages other oncology nurses to consider if the practice is right for their institution. It’s a simple change that can make a big difference in the quality of care provided.

“If you have an EMR at your facility, learn how to put an image in your note and share your note with various providers,” Hillson says. “From there, it is just a matter of having the digital camera available.”

Ultimately, oncology nurses like Hillson are making their voices heard to affect institutional change for their patients. If you notice an area of care where you can make a difference, speak up and share your ideas. You never know when you could change your practice for the better.