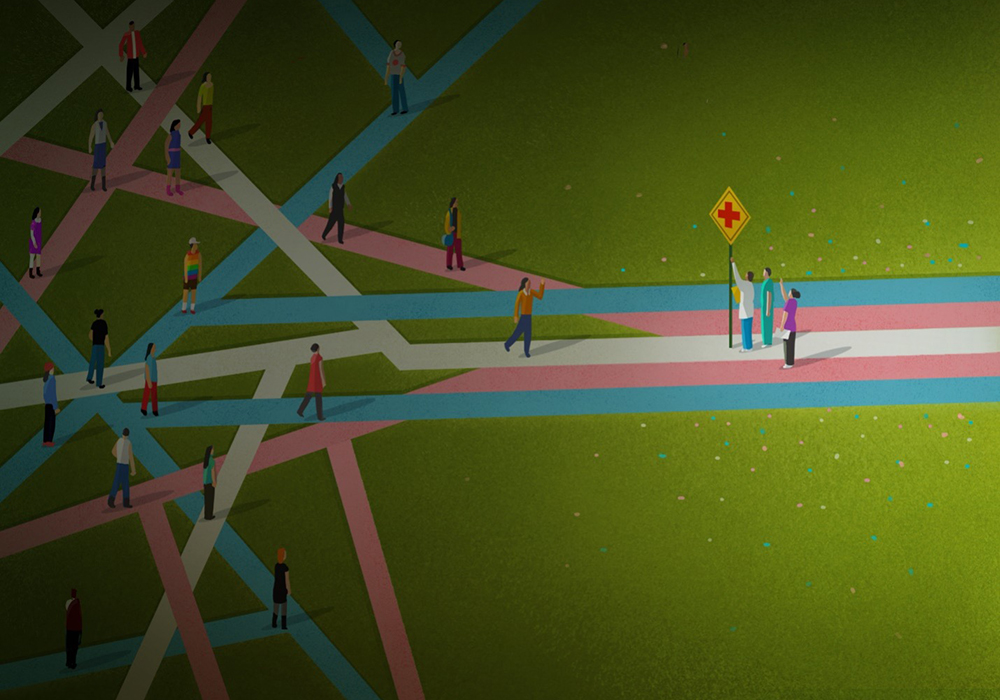

Transgender individuals often experience poor health outcomes, particularly when it comes to cancer. Compared with cisgender individuals, transgender individuals may be diagnosed with cancer at later stages, be less likely to receive treatment, and have worse survival for many cancer types. The disparities extend to survivorship, where transgender people report significant unmet needs, including lack of coordination between gender-affirming care and cancer care, oncology clinician understanding of transgender patient care needs, and transgender-specific resources.

“Transgender patients are considered sexual and gender minorities, and oncology nurses are vital in understanding their unique needs as they move through the healthcare system,” ONS member Georgina (Gigi) Rodgers, BSN, RN, OCN®, NE-BC, director of clinical cancer services at Taussig Cancer Center at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and president of the ONS Cleveland Chapter, said. “It is common for transgender patients to avoid seeking health care and disclosing their sexual orientation and gender identity because of fear of discrimination and poor treatment.”

Transgender individuals report experiencing marginalization from bias, discrimination, and sociopolitical barriers throughout the healthcare system, even with their health insurance coverage.

“Transgender individuals have a unique cancer care experience because our systems of care reinforce gender expectations that create barriers to affirming cancer care. Though there is no universal experience, transgender patients are more likely to be mistrustful of healthcare systems and providers because of prior discrimination and violence,” ONS member Liz Arthur, PhD, APRN-CNP, AOCNP®, nurse scientist at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, assistant professor at The Ohio State University College of Nursing, both in Columbus, and member of the ONS Columbus Chapter, said. “The good news is that we can take action to make our cancer care spaces welcoming environments for transgender people.”

Understand Transgender Patients’ Unique Challenges and Barriers

This patient population frequently confronts health disparities and barriers spanning the cancer continuum. Arthur explained that transgender individuals often report being denied health care or having negative experiences with healthcare providers related to their gender, leading to medical mistrust and delays in seeking care and treatment.

“It is also important to consider the compounding issues of racism, transphobia, and ableism into the oppressive influence on these patients,” Rodgers said. Those issues present barriers to cancer care before a patient even steps foot into a healthcare setting, and healthcare professionals must assess for such situations and intervene with resources or referrals. For example, Rodgers said that her cancer center cared for one transgender patient who had to use a ridesharing service to get to their appointments.

“The patient would insist on scheduling treatment early in the day because she did not want to use a rideshare service after dark in the city as a transgender woman. She felt it was unsafe,” Rodgers said. “Learning of her fear compounded with her diagnosis was eye-opening.”

A lack of gender-inclusive resources for transgender and nonbinary patients with cancer is another barrier to high-quality care. Arthur advised developing all-gender restrooms and waiting rooms; medical forms and records that reflect the patient’s chosen name, pronouns, gender, and an organ inventory and history; inclusive signage and marketing materials; and inclusive patient education materials and resources.

Arthur recalled one nonbinary patient’s experience from her research in patients with breast or chest cancer who are part of the LGBTQ+ community. The patient used they/them pronouns and was being seen by a gender-affirming clinician for evaluation prior to top surgery to create a gender-neutral chest contour.

“The patient was found to have breast/chest cancer after having a mammogram in preparation for surgery,” Arthur said. “They were sent to the cancer center for treatment, and while they were treated with respect by most providers, the breast cancer care delivery model—from using correct pronouns to making recommendations for breast reconstruction—was not affirming to their gender identity.”

Arthur explained that the patient found it difficult to understand that they were not going to be able to have cancer treatment surgery with their top surgery, resulting in a feeling of loss of control and little to no support for finding support groups or systems that knew what they were going through. The patient said that they struggled in a system that was “used to dealing with cisgender or straight women.”

Combat Implicit Bias and Barriers

Implicit or unconscious biases can lead to inequity in access to care and treatment and, subsequently, patient harm. Arthur and Rodgers said that oncology nurses can lead the interprofessional team by example through training, education, and holding one another accountable.

“Nurses can share best practices for the care of transgender patients with cancer and ‘call in’ colleagues who display discriminatory or insensitive behavior,” Arthur said. “Calling in is generally done in private with the intent of providing constructive feedback and differs from calling out, which is often a public shaming of another person.”

Rodgers provides the clinical and nonclinical teams at her cancer center with education, training, and resources about the care of transgender and other LGBTQ+ patients with cancer. She recommended that healthcare professionals take an implicit association test to help identify possible biases and work toward combatting them.

“Our health system also has unconscious bias educational programs available to help caregivers become aware of and mitigate unconscious stereotypes that may affect quality of care,” Rodgers said. “We also educate caregivers about the value of inclusive care for LGBTQ+ patients with cancer, including terminology, definitions, social determinants of health, clinical risk factors, common healthcare disparities, and some strategies for the provision of inclusive care.”

Arthur added that “even clinicians who feel relatively comfortable caring for sexual minority patients report needing more training in the unique care and needs of transgender individuals.” Her institution has a diversity, equity, and inclusion task force for both its main medical center and cancer center, in addition to a chief health equity officer, and it promotes staff and clinician training about implicit bias and cultural competency.

Support Transgender Patients With Inclusive Communication

Creating a safe and affirming environment is one of the many ways healthcare professionals can help transgender patients overcome barriers to obtaining high-quality care during a time when they feel most vulnerable. The key lies in appropriate and inclusive communication—spoken or unspoken. For example, at both Rodgers and Arthur’s institutions, healthcare professionals can choose to display their pronouns and the LGBTQ+ rainbow on their badges, which offers patients a visual cue of safety and inclusion. If a healthcare professional chooses to display this on their badges, they should be confident in their ability to fully support the patient population’s needs.

Using inclusive and appropriate language with your patients, including asking for a patient’s name and pronouns, inquiring about sexual orientation as needed, differentiating gender identity from sex at birth to ensure you can provide inclusive and complete care for the patient, and any medical or surgical gender-affirming steps they have taken as needed, is critical when collecting information. At Taussig Cancer Center at Cleveland Clinic, Rodgers educates her teams on the use of inclusive language and appropriate pronouns and includes scenarios they might see in practice.

For example, nurses may see a patient whose gender presentation does not match what their driver’s license or health record says. Rodgers also goes over communicating by using inclusive language, such as asking a patient “Who is here with you today?” instead of “Is this your husband with you today?”

Oncology nurses should also be aware of appropriate language when discussing a patient’s anatomy, as the discussion may be complicated by a disassociation with the organs present at birth, Rodgers said.

“Ask transgender individuals what terms they would use for their anatomy,” Arthur suggested. “For example, a transgender man or nonbinary person who was assigned female at birth who is in a breast cancer clinic may refer to their anterior torso as their chest, not breasts.”

The psychosocial considerations to assess a patient’s well-being, support network, and social needs can also spark sensitive or stressful feelings for patients, and it may be helpful to bring in members of the interprofessional team to support your patients’ psychosocial wellness. Additionally, oncology nurses may want to consider including any healthcare professionals who helped care for or supported the patient during their transition, if applicable.

“Collect a complete social history to include socioeconomic, substance abuse, depression screening, transportation, and other social determinants of health history and be prepared to connect the patient with appropriate resources such as social work, support groups, financial counselors, smoking cessation classes, nutrition, and more,” Rodgers said.

Use Gender-Related Information in the Electronic Health Record

Oncology nurses should record and encourage other members of the interprofessional team to review the pertinent information regarding a patient’s stated name, gender identity, sexual orientation, and organ inventory in the electronic health record, although not all systems have fields for the data yet, Arthur said. She advocated for and received National Cancer Institute grant funding to change that.

The grant funded a study to increase sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in the electronic health record. Recording the information not only helps healthcare providers to use correct language when engaging with a patient but also evaluate health disparities among the patient population to improve personalized cancer care, Arthur said.

“Our institution is assessing multilevel barriers associated with sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in the health record and implementing factors such as feasibility, acceptability, and data completeness,” Arthur said. “Our study’s results will have a significant impact on members of the LGBTQ+ community by making this data available to other researchers and nurse scientists, addressing barriers to sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in a large comprehensive cancer center, and informing compassionate and inclusive cancer care.”

Rodgers’s institution also records sexual orientation and gender identity in the electronic health record. Healthcare professionals can document a patient’s stated name, sexuality, legal sex, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, patient pronouns, affirmation steps a patient has taken to align with their gender identity, and organ inventory.

“When oncology nurses and other healthcare providers view appointment lists, schedules, demographic data, and chart review, they can easily see every patient’s preferred name and pronouns. We can also add columns to our schedules that highlight whether a patient’s sex assigned at birth differs from their gender identity,” Rodgers said. “In the event that a member of the interprofessional team may not have been apprised of the information, our teams perform daily huddles to review pertinent information.”

Consider Transgender Patients’ Unique Care Needs

Taking an organ inventory is critical to identifying the exams that transgender patients require throughout cancer treatment, such as prostate, Pap, and pregnancy tests. Using comprehensive and inclusive language and asking open-ended questions to conduct those assessments is vital.

At Rodgers’s institution, the electronic health record can document an organ inventory and surgical or hormonal gender affirmation steps. She explained that if a transgender patient has a cervix, uterus, or prostate, the organ should be screened according to established guidelines, and lab samples should be clearly labeled to indicate the organ and whether the patient is on hormones, the type of hormones, and whether the patient has a menstrual cycle.

“Special considerations for physical examinations and appropriate cancer screening techniques for transgender individuals take into account possible anatomical dysphoria, history of gender-affirming procedures (e.g., vaginal examination for a transgender man), and trauma-informed care,” Arthur said. All patients require appropriate screening for their current anatomy, regardless of gender. Although transgender-specific cancer screening guidelines are limited because of a lack of large-scale research studies, Arthur uses the University of California, San Francisco’s, guidelines for gender-affirming care and applauded the resource.

“As clinicians, we should avoid assumptions about patient preferences based on gender, sexual orientation, age, race or ethnicity, or other personal identity,” Arthur said. “Oncology care should be patient centered, and that requires understanding patients’ values, preferences, and lifestyle to develop a personalized care plan through shared decision making.”

“Understanding the overall health risks of the transgender community and the reasons for disparities in health care can assist care providers in engaging with patients,” Rodgers said. “Use of inclusive language, building trust, and getting to know the whole patient from a physical, psychosocial, and sexual health dimension can provide for truly holistic care.”