More than one billion individuals worldwide have some type of disability, and the population often faces higher rates of cancer, social determinants of health disadvantages, and greater health disparities. They are also more likely to have risk factors associated with a cancer diagnosis and require close care after a diagnosis that accommodates for their disability.

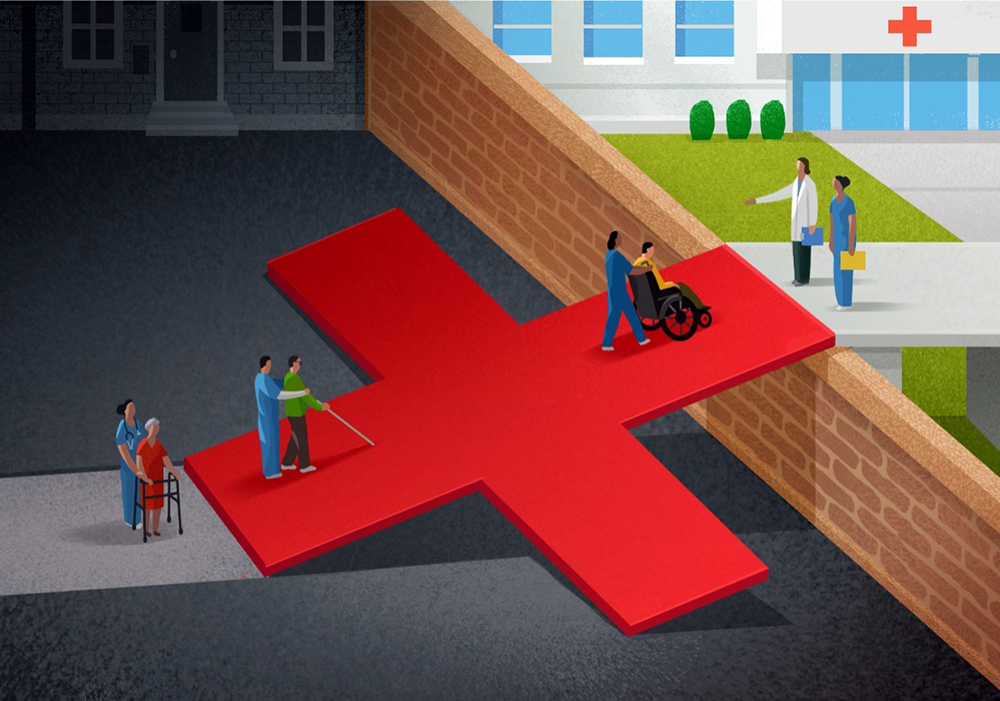

Since its adoption in 1990, the Americans With Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities to ensure that people with disabilities have equal rights and opportunities, including in healthcare environments. However, barriers exist in the healthcare industry, preventing or making it difficult for patients with disabilities to seek and receive equitable care.

“Disabilities are extremely diverse,” Lisa I. Iezzoni, MD, MSc, 2022–2023 Sally Starling Seaver Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, MA, said. “The rate of having a disability increases with aging, as does the rate of cancer. There are multiple reasons why people with disabilities might risk developing cancer.”

Systemic Factors Limit Patients’ Access to Care

Physical, communication, and other barriers to obtaining cancer screening, services, timely diagnoses, and appropriate treatment lead to cancer care inequities for people across diverse disabilities. Also contributing to disparities are social determinants of health factors such as “high rates of poverty and unemployment, low educational status, substandard housing, greater exposure to toxic environments, and limited or no access to transportation.”

In fact, Iezzoni, in collaboration with a team of researchers, concluded in a 2022 The Lancet article that “people with disabilities are more likely than those without disabilities to report a lack of access to healthcare services and having unmet healthcare needs.” Iezzoni has interviewed more than 300 people with varying disabilities for her research and identified multiple barriers to health care and cancer care.

ONS member Grace Cullen, DNP, FNP-BC, AOCNP®, ACHPN, PMGT-BC, Metro Detroit ONS Chapter secretary, is a hematology/oncology and palliative care/hospice nurse practitioner at John D. Dingell VA Medical Center’s department of medicine and an adjunct clinical instructor in the advanced practice program at Wayne State University College of Nursing, both in Detroit, MI. Cullen cares for veterans with physical disabilities, including individuals who use wheelchairs or have a mobility disability, who are blind, and who are deaf or hard of hearing, which is one of the most common service-connected disabilities among veterans. Hearing as well as vision loss can also be associated with traumatic brain injury and contribute to balance issues because of an interrelated sensory system.

Lack of Disability-Appropriate Resources: Cullen said that in her experience, patients who are blind may not have appropriate printed materials and resources on their diagnosis or treatment plan and may face difficulties with referrals to unfamiliar facilities for evaluation and treatment. For patients who are hard of hearing or deaf, it can be difficult to communicate spoken instructions and ensure accurate understanding during cancer care.

Patients with cancer who also have a mobility disability or who use wheelchairs may not qualify for certain cancer treatments or screenings because of their functional status, Cullen said. In addition, certain treatments may affect their quality of life by causing sequela that a person without a mobility disability would not experience. Iezzoni said that weight gain from certain drugs, for example, could affect the patient’s position in their wheelchair and increase the likelihood of pressure injuries.

Cullen said that healthcare professionals must consider and accommodate limitations and difficulty in cancer screening and procedures. Cullen assesses the availability of the following when caring for a patient with a physical disability in her practice:

- Adaptive equipment for locomotion for patients with mobility disabilities, as well as adaptive equipment for sensory impairments, such as hearing aids, pocket talkers, eyeglasses, magnifying glasses, and writing boards

- Transportation that accommodates physical disabilities

- The patient’s support system or caregiver at their home or in their community

Negative Experiences: Iezzoni recalled interviews with several patients who are hard of hearing or deaf about their experiences with receiving cancer screening. In one focus group comprised of women who speak American Sign Language (ASL), moderated by an ASL interpreter, one young woman described having recently received her first Pap test.

“Her doctor failed to secure an ASL interpreter for the physical exam,” Iezzoni said. “She had no idea what a speculum was, when it would be inserted, and what it was going to be like. It was heartbreaking. She was saying things like she was never going to go again.”

Another woman came out with bruises after her mammogram because she was unable to hear the technician instructing her to hold her breath during the test and it had to be conducted multiple times, Iezzoni explained.

Biases: Healthcare professionals also require heightened awareness of implicit bias at all points of care. Iezzoni said that some patients with disabilities may experience diagnostic overshadowing, which is “the attribution of symptoms to an existing diagnosis rather than a potential comorbid condition,” delaying an accurate diagnosis and appropriate care.

Communication Identifies Challenges and Solutions

To combat health disparities and implicit biases, Iezzoni and Cullen both emphasized the importance of open communication with patients and asking them about their disabilities and any concerns they foresee with their cancer care. “Talk to your patients about where they live, their challenges of daily living, and their instrumental activities of daily living before they had cancer. And then ask, ‘For most patients, this treatment causes these side effects. How do you anticipate that these will affect your life at home?’” Iezzoni said. “Once you’ve talked to the patient about the side effects, you can say, ‘Okay, can you tell me what you think the biggest side effects are, and what things you are especially going to be looking for when you get home?’” By reviewing this information, oncology nurses and the overall interprofessional team can ensure that the patient hears and understands their treatment and its implications, Iezzoni said.

An in-depth understanding of a patient’s disability and possible challenges in receiving cancer care can help oncology nurses discover solutions to major problems. For example, in Cullen’s practice, when a disabled patient with cancer who is undergoing treatment or follow-up care lacks a support system, they are “referred to social work for community resources, such as Meals on Wheels and transportation options. And short-term inpatient admission is arranged during the course of their treatment, such as palliative radiation therapy, for patients who qualify.”

But the biggest takeaway, Iezzoni and Cullen agreed, is to listen to the patient and involve them in treatment planning and decision making. Talk to patients about their cancer care challenges; then, uncover solutions: If they’re transitioning to a new facility for treatment, have them visit the new treatment area beforehand to identify and address any concerns. Assess their ability to use a nurse call button, and find other methods they can use to get the interprofessional team’s attention if needed. “During any patient encounter, it is also important to give the patient the chance to verbalize their understanding of what you have discussed and provide the opportunity for questions or clarifications,” Cullen added.

Comprehensive Assessments to Enable Higher Quality Care

Conducting a thorough patient assessment, including their history and how they’re doing at home, enables nurses to identify patients’ support systems and available resources, Cullen said. She then collaborates with the interprofessional care team to address the concerns through referrals. In her practice, Cullen has worked with:

- Audiology to assist patients with hearing disabilities with adaptive equipment such as hearing aids and pocket talkers

- Eye clinics to assist patients with visual disabilities

- Physical therapy for patients with mobility disabilities for evaluation and assistance with care, including possible adaptive mobility equipment

- Occupational therapy for patients who could benefit from adaptive home equipment

- Social work for patients with limited support for meals, transportation, community resources, and possible sources for financial assistance

Iezzoni suggested that oncology nurses repeat the assessment process each time they see the patient and emphasized the importance of sharing the results with the interprofessional team to ensure that new symptoms and side effects and any other challenges are managed appropriately and quickly. Nurses should also consider asking the patient for permission to involve their caregivers and personal care assistants in the assessments.

“Cancer treatment can be extremely disabling,” Iezzoni said. “If a person with preexisting disability is diagnosed with cancer, clinicians can anticipate that the typical disabling consequences of treatment may be even more exaggerated.”

“Nursing, as a profession, needs to be at the forefront of improving the care of patients with cancer who also have physical disabilities by being engaged in education, research, advocacy, and clinical care,” Cullen said.