By John Hillson, RN, BSN, OCN®

November 7, 2022, is the 155th birthday of Maria Sklodowska, who is better known as Madame Marie Curie, one of the greatest minds of chemistry, physics, and radiation oncology. The day also marks the fifth anniversary of #WomenWhoCurie, a social media campaign from the Society for Women in Radiation Oncology (SWRO) that supports and increases visibility of women in radiation oncology.

Curie’s accomplishments were many, but so were the barriers she faced. Although she was a bright student and raised by a science teacher, Curie was denied advanced education in occupied Poland because she was a woman. She continued her education as best as she could illegally, then relocated to France to finally attend university. Overcoming limited understanding of the French language, minimal funds, and systemic sexism, she quickly obtained degrees in physics and mathematics. Curie intended to return to Poland as a teacher but was again denied the opportunity because of her gender. She stayed in Paris, married her husband Pierre Curie, and considered a doctoral thesis.

Curie’s era was an exciting time in the radiation field. Röntgen discovered x-rays, and medicine was changed overnight forever. Weeks later, Becquerel discovered that uranium emits invisible rays with similar properties. Curie chose to study Becquerel radiation.

She developed methods to measure, extract, and refine radioactive substances and proved that thorium was radioactive. She determined that radiation was a property of individual atoms and coined the term “radioactivity.” She defended her thesis in 1903, becoming the first woman to receive a doctorate in France, and she also earned the Nobel Prize in physics that year along with Becquerel and her husband. Her contribution was initially ignored, but her husband fought for her recognition. Curie (Ci) and Becquerel (Bq) are units of measure for radioactivity still used today.

The Curies provided the radium for the first brachytherapy procedure in 1901; in fact, curietherapy is another name for brachytherapy. Radium therapy started at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in 1903.

She earned a second Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1911 on her own for her discovery of two new elements: polonium (named after her homeland) and radium. Both elements are hundreds of times more radioactive than uranium, but radium in particular was used for radiation therapy.

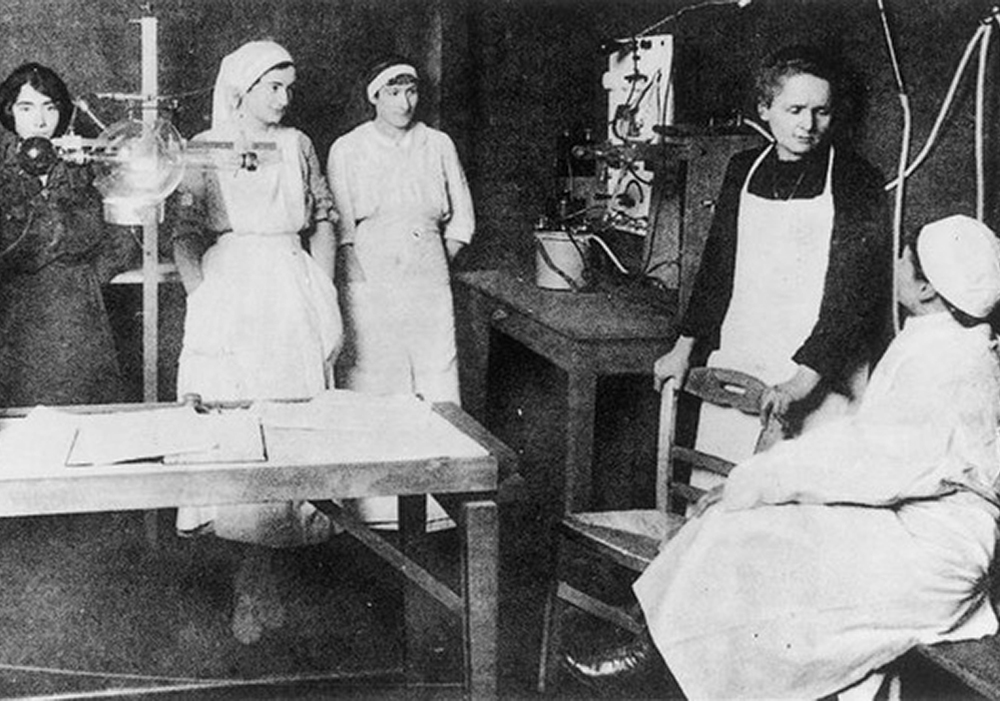

During World War I, Curie hid her radium samples and stopped her research. She worked with her daughter to create hundreds of standing x-ray facilities in France as well as a fleet of mobile x-ray vehicles called petite curies. She trained 150 women to operate the equipment, then herself learned to drive so that she could directly assist in the care of wounded soldiers on the frontlines. Her efforts helped an estimated million soldiers, and she later wrote a textbook on wartime radiology and radiology safety.

On principle, Curie declined to patent the radium refining process, but when the price exploded to $100,000 per ounce she could no longer afford to study the element she had discovered. A group of American women, forerunners of the American Association of University Women, mobilized to raise funds for a gift of 1 ounce, which President Harding bestowed to Curie.

Curie lived to see Irene Joliot-Curie and her husband create the first artificial radioactive isotope but died before her daughter won her own Nobel Prize for making medical radioisotopes safer to obtain and more readily available. In 1934, the year Curie died, the international and American communities announced safe occupational radiation exposure levels for workers for the first time.

Curie remains the only woman to win two Nobel Prizes and the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields. She was also the first female lecturer and professor at the University of Paris. Both Marie and her husband were constantly ill from radiation sickness, and her death from aplastic anemia in 1934 at age 66 was likely the result of persistent radiation exposure. A few of Curie’s books and papers are still so radioactive that they are stored in lead boxes. It seems fitting that Curie left a scientific legacy that is literally untouchable.

#WomenWhoCurie was started in 2017 on Marie Curie’s 150th birthday to celebrate her pivotal work and many accomplishments. However, the day is about much more than an extraordinary intellect and trailblazing life. It is a celebration of her living legacy: the many contributions of the brilliant and dedicated professionals in radiation oncology today who are working toward gender equality in this very rewarding specialty.

To create a more inclusive environment and uplift all voices in radiation oncology, SWRO shifted the campaign from #WomenWhoCurie to #WeWhoCurie and encourages all individuals to participate. It is a celebration of each and every one of us. It is a celebration of you.

How do you plan to promote #WeWhoCurie? A female physicist recently made headlines for creating 1,750 Wikipedia pages for female scientists who lacked biographies highlighting their contributions to their fields, but no actions are too big or too small. Share your story with other oncology nurses on the ONS Communities.