Nursing Considerations for Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

By Clara Beaver, MSN, RN, AOCNS®, ACNS, BC

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among those assigned male at birth, with one in eight diagnosed during their lifetime. But with five-year survival rates of 90%, it’s also one of the most successful cancers to treat (https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf), making survivorship care even more important.

Many patients live with the disease or receive long-term maintenance therapies, and patients often have comorbidities prior to diagnosis. With the advancements in treatment, many (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors) are outliving their prostate cancer diagnosis and their death is related to other comorbidities. Survivorship care requires (https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4888) an interprofessional approach that involves (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557) primary care, urology, and oncology specialists to address the wide range of late and long-term effects and comorbidities.

Late and Long-Term Effects

Because each prostate cancer therapy is associated with different late or long-term effects, oncology nurses need to understand and consider treatment options when coordinating the survivorship care plan. Patients may receive watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), chemotherapy, or any in combination.

Surgical removal of the prostate (radical prostatectomy) is used for cancer that has not spread outside of the prostate gland. Radiation is used if the patient has low-grade disease that remains in the prostate gland and they do not want surgery; it’s also an option in combination with hormone therapy for metastatic disease or if the cancer is not completely removed or recurs after surgery.

ADT uses hormones to reduce androgen levels that would otherwise fuel prostate cancer cells. It’s used when disease has spread too far to be cured by surgery or radiation or if it recurs after treatment. It may be appropriate in combination with radiation for high-risk disease or to shrink a tumor before radiation to make treatment more effective.

Chemotherapy is used for metastatic disease not responding to hormone therapy; it is not standard treatment for early-stage disease, but it has been shown to help patients live longer and slow the growth of cancer. Agents typically used are docetaxel (most commonly used in combination with steroids as the first treatment option), cabazitaxel, mitoxantrone, and estramustine.

Immunotherapy, which stimulates the body’s immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells more effectively, is a newer approach for advanced prostate cancer. Sipuleucel-T uses a patient’s own T-cells, which are harvested through apheresis, combined in a lab with prostatic acid phosphates, and reinfused over three doses. Called a cancer vaccine, it does not cure prostate cancer but may extend survival after treatment.

Another immunotherapy option is the PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor drug pembrolizumab. Immune checkpoint inhibitors tell the body when to turn on an immune response and are used when the cancer starts to grow again after chemotherapy. Pembrolizumab blocks PD-1 on T cells and boosts the immune response against cancer cells. Researchers are continuing to study its effects in prostate cancer.

The PARP inhibitors rucaparib and olaparib are targeted therapies for advanced prostate cancer. They attack the cancer cell while doing little damage to healthy cells by blocking (https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating.html) the PARP pathway, inhibiting tumor cells with BRCA variants from repairing damaged DNA, and leading to cell death.

As many as 20% of prostate cancer survivors reported treatment-related regret because of ongoing side effects, which include sexual dysfunction, urinary incontinence, bowel issues, depression, and anxiety and often are exacerbated by comorbidities. ADT is associated (https://smhs.gwu.edu/gwci/sites/gwci/files/NCSRC%20Toolkit%20FINAL.pdf?src=GWCIwebsite) with hot flashes, anemia, obesity, osteoporosis (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557), and fractures (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors).

Patients also often report (https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4888) employment, insurance (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557), and financial issues (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors) or fear of the unknown future.

Ongoing Screening and Prevention

Prostate cancer survivors are at greatest risk for disease recurrence (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf) in the first five years after treatment, in addition to secondary cancers. Providers should consider screening (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf) for individuals who may be candidates for genetic testing, especially those with indications of a hereditary cancer syndrome based on personal and family history.

Lifestyle recommendations include lifelong smoking and alcohol cessation. Advise patients (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf) to maintain a diet high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low in fat, processed foods, and red meat and include an intake of at least 600 IU of vitamin D per day. Patients should engage (https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4888) in regular exercise (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf) and maintain a healthy body weight (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors).

Cancer survivors should follow recommended cancer screening guidelines and other screening recommendations. Those with a smoking history may be candidates for a lung cancer screening program.

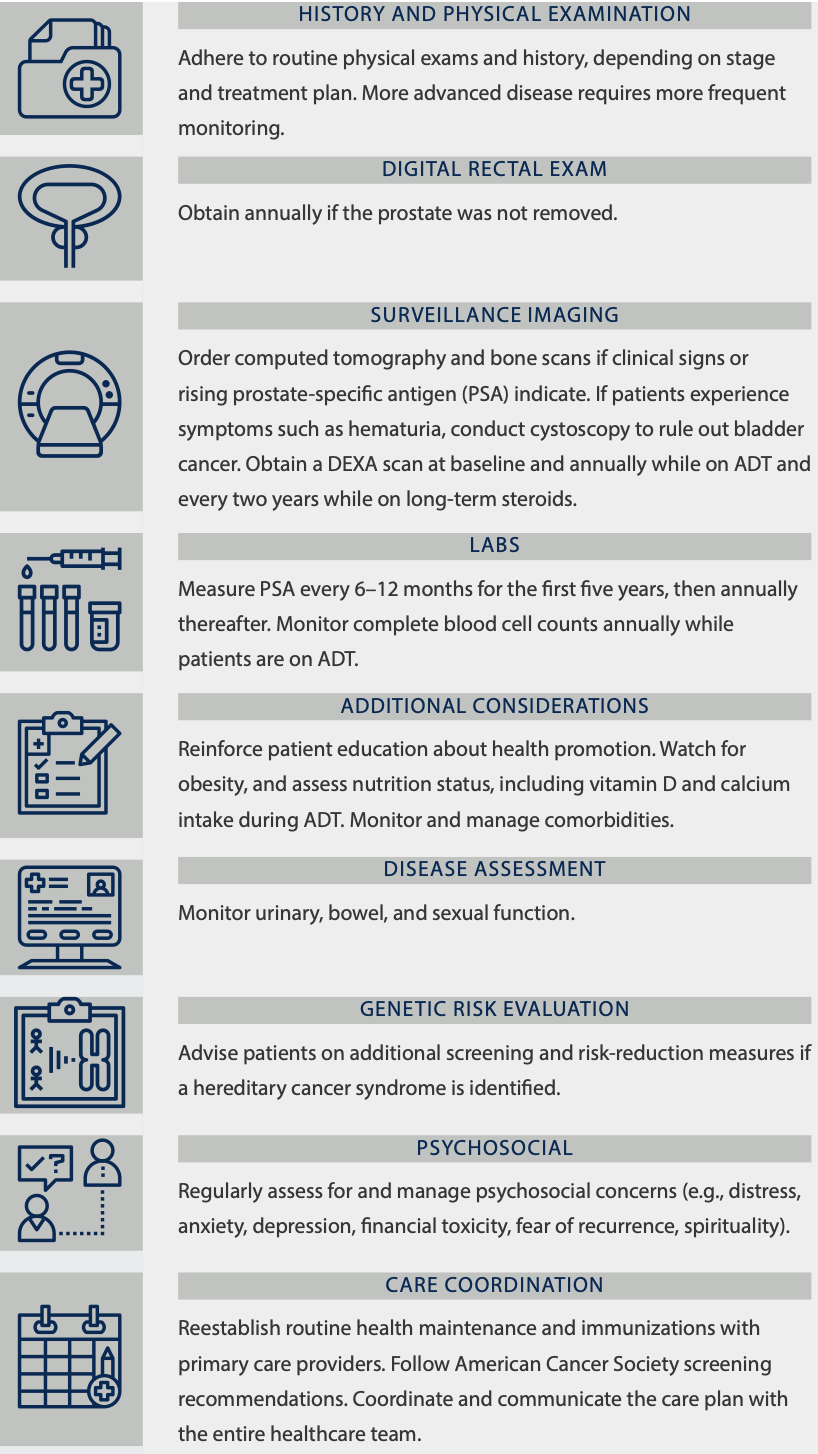

Sample Prostate Cancer Survivorship Plan

Note. Based on information from George Washington University Cancer Institute and American Cancer Society (https://smhs.gwu.edu/gwci/sites/gwci/files/NCSRC%20Toolkit%20FINAL.pdf?src=GWCIwebsite), Resnick (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557), Skolarus (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-approach-to-prostate-cancer-survivors), and NCCN (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf).