Nursing Considerations for Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care

As the third most common cancer (https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html) among both men and women, colorectal cancer is a reality for the more than 1 million people in the United States who are living with or have a history of the disease. Advancements in early detection and treatment have improved outcomes, but many survivors experience late and long-term side effects that may vary in duration, intensity, and impact on their quality of life. Clinicians must tailor (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf) each survivorship care plan for a patient’s cancer type, stage, treatment received, psychosocial implications, and side effects or toxicities. Studies have shown (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2049-3) that experiencing long-term side effects and symptoms can reduce survivors’ quality of life.

Late and Long-Term Effects

Treatment modalities, specific drugs, and dose all influence potential toxicities. Long-term side effects from colorectal cancer surgery include (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286) pain, tissue scarring, body image concerns, diarrhea, and incontinence or urgency with defecation. A temporary or permanent ostomy may be required, and referral to ostomy specialists or ostomy management can help to optimize side-effect management. Radiation side effects are determined by the specific location of the treatment received. Side effects include (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286) fatigue, skin changes, diarrhea, strictures, and lymphedema.

Chemotherapy side effects are related to the specific agents used but generally include fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, fertility problems, sexual changes, diarrhea, and cognitive effects. Late side effects, which are less common, include (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286) secondary cancers such as myelodysplasia and leukemia. Immunotherapy (i.e., checkpoint inhibitors) may cause immune-mediated side effects to any tissue or organ in the body, including colitis, pneumonitis, and dermatitis. Use of targeted drugs for specific tumor genotypes may present additional side-effect profiles that should be considered when developing the plan of care.

In addition to physical effects, providers should routinely assess (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286) survivors’ psychosocial effects, including distress, anxiety, depression, fear of recurrence, financial toxicity, spirituality, and career and personal role changes.

Ongoing Screening and Prevention

Colorectal cancer survivors are at risk (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf) for disease recurrence and development of other colorectal tumors or secondary cancers, and screening and preventative care recommendations should consider patients’ comorbidities and family history. Encourage patients to follow healthy lifestyles (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21591), including exercising regularly, maintaining their ideal body weight, stopping smoking, limiting alcohol consumption, and practicing sun safety. Include (https://www.uptodate.com/contents/the-roles-of-diet-physical-activity-and-body-weight-in-cancer-survivors) a diet high (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf) in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21591) in fat, processed foods, and red meat. Colorectal cancer survivors should follow the recommended screening guidelines for other cancers as appropriate for their age and gender.

Because of its association with several hereditary cancer syndromes, assessing patients’ personal and family history for genetic implications is an essential part of care. Factors suggestive of a hereditary cancer syndrome include (https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colon-treatment-pdq) young age at diagnosis, multiple primary cancers, and a personal history of associated cancers such as endometrial.

Obtain routine colorectal tumor testing (https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colon-treatment-pdq) for DNA mismatch repair deficiency or microsatellite instability to determine whether additional genetic testing is warranted (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf). Approximately 5% of colorectal cancers are associated (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1322) with a germline variant, which can help clinicians guide patients and families with a hereditary cancer syndrome. Those with familial adenomatous polyposis (https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/genetic-disorder-reference-sheet-lynch-syndrome-hereditary-nonpolyposis-colorectal), Lynch syndrome, or other cancer syndrome will follow a specific care plan (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf) with additional risk reduction, screening, and early detection strategies. Collaboration with a genetic counselor or specialist will identify a comprehensive care plan.

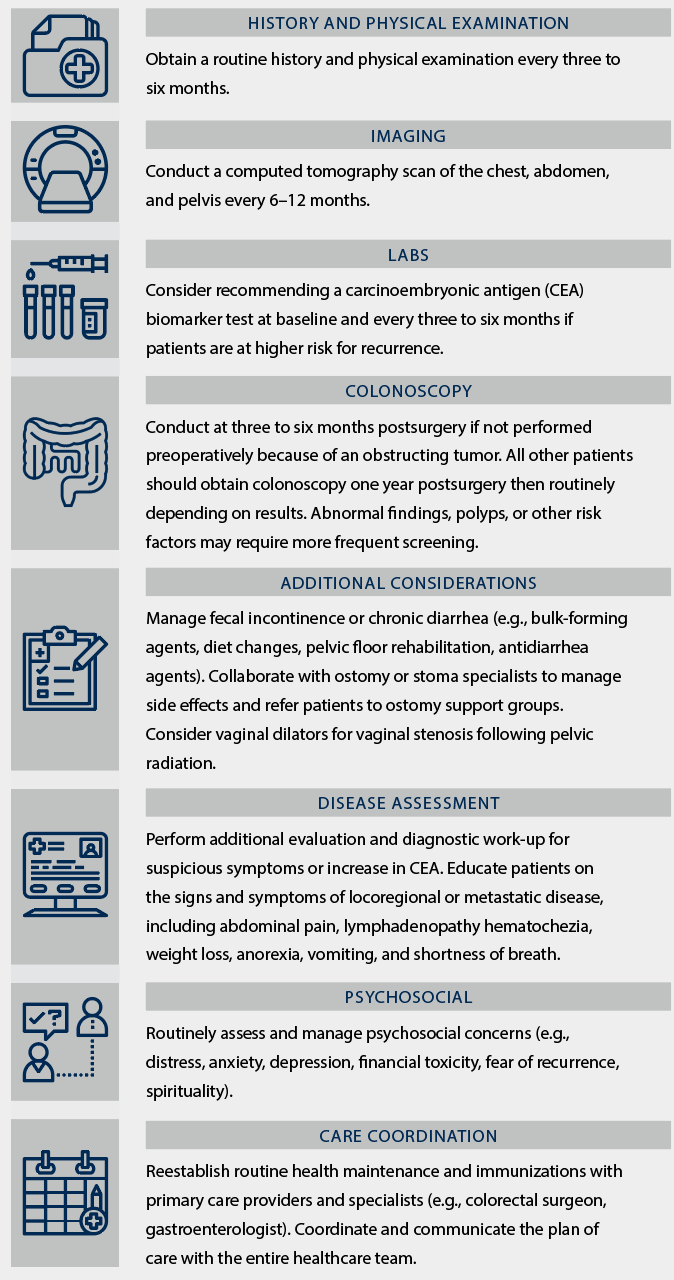

Sample Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care Plan

Note. Based on information from El-Shami et al (https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21286)., Meyerhardt et al (https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7442)., NCCN (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf), NCI (https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colon-treatment-pdq), and Wiltink et al (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05301-7).