As cancer care evolves, so do new opportunities for nursing roles. Oncology nurses in any role provide essential cancer care, including addressing disparities and social determinants of health and reducing financial toxicity. However, what sets nontraditional nursing roles apart are the populations they care for, how they provide that care, and how they’re overcoming systemic disparities to ensure that all patients with cancer have equal access to high-quality oncology care.

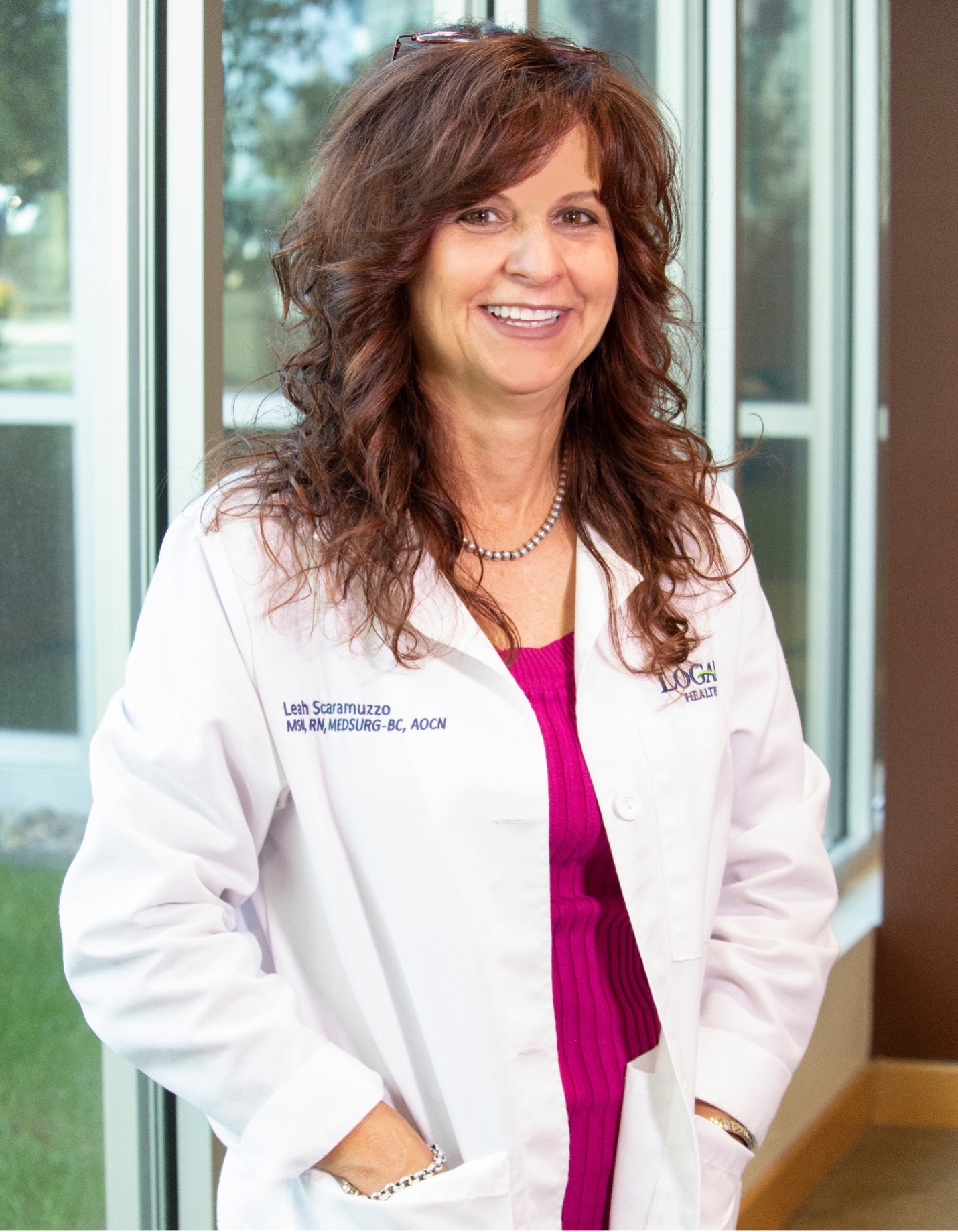

“Nontraditional nursing roles fill a large gap in cancer care and improve patients’ quality of life outside of the healthcare setting by eliminating barriers to care, increasing treatment compliance, helping them navigate the complex healthcare system, and providing patient-tailored education about self-care management strategies for cancer-related symptoms and side effects,” ONS member Leah Scaramuzzo, MSN, RN, MEDSURG-BC, AOCN®, nursing director of oncology clinical development at Logan Health in Kalispell, MT, and a member of the Big Sky ONS Chapter, said. “As the clinical setting becomes busier than ever and the healthcare landscape changes, these roles complement traditional nursing roles.”

Oncology Nurses Have Roles in Every Aspect of Practice

Scaramuzzo explained that nontraditional nursing roles may look like:

- Oral medication management nurses collaborate with pharmacy to review novel oral anticancer medications’ possible side effects

- Telephone triage nurses partner with the social work team to manage patients’ psychosocial distress

- Nurse navigators refer patients to physical therapy for cancer pre- or rehabilitation plans

- Nursing informaticists collaborate with oncology providers to implement new policies, procedures, and order sets

According to ONS member Robyn MacCallum-Bush, RN, BSN, travel oncology nurse based in Great Falls, MT, travel nursing—another nontraditional nursing role—started decades ago during a nursing shortage and exploded amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“With the current nurse staffing shortage and its resulting increased patient acuity, nurses are finding themselves collaborating with nurses in nontraditional roles to address gaps in patient care now more than ever,” Scaramuzzo said.

Travel Nurses Fill the Pandemic’s Staffing Gaps

MacCallum-Bush, who began her journey as a travel nurse in 2006 in her home state of Montana, explained that travel nurses can help permanent staff provide better quality of care, increase patient satisfaction, and experience less burnout.

“As a travel nurse, I find most places I’ve gone are very welcoming and simply happy to have someone who requires very little orientation and can hit the floor running,” MacCallum-Bush said.

Travel nurses must adhere to the same expectations and rules as permanent staff. Although the basics of oncology remain the same, travel nurses must be flexible and ready to quickly learn the different individual facility processes and policies, electronic health records, and layout and inventory of supplies. And the day-to-day practice can look different at each institution.

Travel nurses must get to know the staff, physicians, nurse practitioners, dieticians, and all the ancillary staff involved at a facility, MacCallum-Bush said, emphasizing the importance of professional relationships. “I want the interprofessional team to feel comfortable with me and develop a good rapport and trust,” she said. “I spend time with the physicians when I can and often offer a copy of my resume. I believe it helps them to see my experiences.”

MacCallum-Bush said that ongoing oncology education is essential for travel nurses so they can stay up to date on drug approvals and treatments on their own. MacCallum-Bush herself has completed the ONS/ONCC Chemotherapy Immunotherapy Certificate Course and recommends it for all travel oncology nurses.

“The ONS/ONCC Chemotherapy Immunotherapy Certificate Course is an absolute must for all nurses who are administering chemotherapy,” MacCallum-Bush emphasized. “The course helps to provide knowledge about chemotherapy, side effects, and potential reactions and how to treat them, which all adds up to better quality of care. Most facilities will not allow a nurse to administer chemotherapy without course completion. An OCN® certification is also often requested but doesn’t keep a nurse from being hired as a travel nurse.”

Rural Communities Require Innovative Nursing Strategies and Solutions

Approximately 46 million U.S. residents were living in rural areas in 2020, 14% of the country’s population, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural individuals often face greater difficulties accessing health care and are more likely to die from cancer, heart disease, unintentional injury, chronic lower respiratory disease, and stroke than urban individuals.

Additionally, geographic regions have wide discrepancies in number of oncology providers, and an analysis published in JCO Oncology Practice said that “64% of counties in the United States did not have any physicians specialized in oncology with a primary practice site located in that county and 12% of counties did not have oncologists in the local county as well as the adjacent counties.”

Scaramuzzo cares for rural communities at her frontier area institution, a population whose challenges are often overlooked, she said. According to the National Rural Health Association, several factors are considered when classifying an area as frontier, including population density, distance and travel time to a service or a population center, and access to paved roads. Scaramuzzo’s patients “travel anywhere from two to four hours for their cancer treatment, the nearest grocery store or pharmacy may be 40–50 miles away, and roads are not often plowed in the winter nor are they paved.”

Scaramuzzo said that patients in her practice may be farmers or ranchers who cannot take time away for health care, individuals who lack access to cancer screenings close to home, and individuals with little experience with technology or lack of access to broadband internet.

“As oncology nurses, we all have worked with patients who are affected by poverty, lack of education, drug addiction, mental illness, and lower socioeconomic status,” Scaramuzzo said. “However, we are lacking awareness and discussion about the unique challenges across rural populations.”

Scaramuzzo has also cared for patients living on Indian reservations with limited access to preventive health care and treatment. “During the winter, I worked with a patient and their family that lived on an Indian reservation. Their son had developed neutropenic fever, and the Indian Health Service community hospital on the reservation was not familiar with accessing ports, which resulted in a trip to our hospital, 101 miles away. They shared the story of driving an old van in white-out conditions and the treacherous journey through Marias Pass, a mountain pass on the Northern Rockies more than 5,000 feet high, bordering Glacier National Park.”

Scaramuzzo said that her team was spurred to action to address the geographic social determinant of health. They helped the Indian Health Service hospital obtain port access supplies and a port practice model, shared their central venous access policies, and educated the staff about managing neutropenic fever.

Patients and their families living in rural areas are often unable to drive long distances to daily or weekly treatments or temporarily relocate closer to the treatment center to receive radiation, infusions, treatments requiring hospitalization, or even transplant, Scaramuzzo said. She and her teams work with their institution’s home health program to equip patients and caregivers with appropriate safe handling supplies for the home setting, help them practice accessing ports, and provide patient education resources. She also works with a virtual health team on telemedicine and a marketing team to enhance the patient education materials and resources on her institution’s website.

“Limited access to cancer treatments and providers is a real disparity,” Scaramuzzo said. “Frequently, people living in rural areas delay seeing an oncologist until their cancer is at late stage or even end of life, when cure or stabilization is not realistic.”

Addressing Disparities for Rural Communities

Lack of technology is a barrier to quality care for rural communities, but oncology nurses may be able to help their patients overcome it by recruiting supportive care teams such as telehealth concierges. Scaramuzzo said that Logan Health’s telehealth concierges assist patients in setting up their telehealth platforms and conduct a practice session prior to their first provider visit to troubleshoot any issues and increase patients’ comfort with virtual health care.

To address the gaps in care for rural communities, Scaramuzzo’s institution is also working to:

- Expand services and decrease travel distances: Patients can access a program to help find temporary housing while receiving their cancer treatment, and a mobile mammography coach travels through rural communities to offer breast cancer screenings.

- Alleviate financial burdens, particularly with limited insurance coverage: The prior authorization team has an RN representative, and it identifies patient assistance opportunities while obtaining insurance approvals.

- Open avenues to clinical trial participation: Scaramuzzo and her team are collaborating with their clinical research team to expand trial options for patients with cancer.

- Create partnerships between providers and community leaders: By partnering with two critical access hospitals in the south and west, they are able to provide telemedicine visits, lab draws, and cancer infusion treatments locally and closer to patients’ homes.

Rural Nurses Have Needs, Too

Many rural critical access hospitals lack nursing leadership teams or staff with foundational training and experience in oncology. “Oncology nursing has special educational needs because of rapidly evolving cancer treatments, supportive care, and research findings,” Scaramuzzo said. “In addition, the shift from inpatient to outpatient cancer care means that inpatient nurses have less experience and fewer educational directives in caring for many of our patients.”

Scaramuzzo recommended oncology nursing solutions:

- Develop a tool for nurse communication and information sharing.

- Create a chemotherapy/immunotherapy clinical practicum to provide hands-on opportunities.

- Offer nursing consultative services.

- Provide access to oncology evidence-based practice standards, guidelines, and recommendations and tools and resources for nurses working in rural areas.

“Interventions to address gaps in care for rural patients are slowed, and focusing on this population is critical,” Scaramuzzo said. “As many people move away from cities now that remote work opportunities are readily available, nurses will more than likely cross paths with rural patients.”

Advice From Nurses in Nontraditional Roles

“For any nurses who are interested in being a travel nurse, make sure you are very flexible, open-minded, easy-going, and willing to ask questions. Start somewhat close to home so you know how you will feel being away from family and friends,” MacCallum-Bush said.

For permanent nurses who work with travel nurses, she added, “Realize that most of us have left our families behind, and it’s rare to know anyone close by. Involve us in group activities, tell us about your city and what we can do, where to go or not to go, and good restaurants. Help us adjust to a new and different place. Everywhere is an adventure.”

“Today is one of the great times in nursing to be an entrepreneur in the profession,” Scaramuzzo said. “Look for gaps, think of out-of-the-box solutions to provide exceptional patient care, complete your needs assessment, and write a proposal regarding how a new or unique nontraditional nursing role can support those providing day-to-day hands-on care. Our nursing shortage will only exacerbate; leveraging our expertise in developing strategies to assist in providing care may be the answer for supporting our frontline healthcare workforce shortage.”