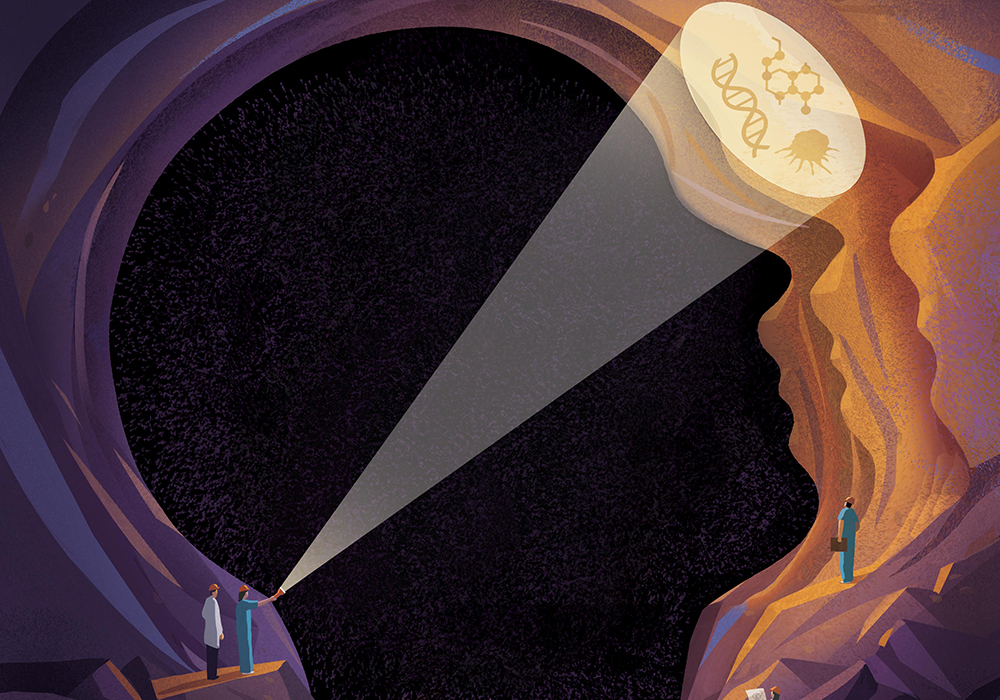

With the growth of genomics and targeted therapy, nurse scientists are gaining deeper understanding the vast facets of patients’ symptom experience, and biosignatures could be the key to unlocking the next frontier in symptom science research.

The discoveries are already finding their way to clinical practice, too. Nurses at the bedside and chairside are using patients’ biosignature data to tailor their symptom management strategies, provide the best possible care, and achieve better outcomes.

What Is a Biosignature?

Biosignatures are the biologic changes, characteristics, and elements of past or present symptoms, ONS member Nada Lukkahatai, PhD, MSN, RN, CNE, FAAN, assistant professor of nursing and director of the research honors program at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD, and member of the Greater Baltimore ONS Chapter, said.

ONS member Komal Singh, RN, PhD, assistant professor of nursing at Arizona State University in Tempe, nurse scientist at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, AZ, and member of the Phoenix ONS Chapter, said that oncology nurses are familiar with biomarkers such as prostate-specific antigen or the factors that predictive tests like the Breast Cancer Index uses. However, oncology nurse scientists are trying to use the concept of a biosignature to identify patients with a higher symptom burden.

“If successful, one could imagine oncology nurses assessing their patients’ level of a symptom like fatigue prior to treatment by measuring predetermined biosignatures that predict patients who will experience intense symptoms during treatment,” Singh said. “With this information, patients could be informed of their fatigue trajectory and initiate interventions to prevent or treat the symptom.”

Lukkahatai echoed the opportunity for personalized health care.

“Symptom science can be a complex and subjective aspect of oncology, and clinicians often rely on our patients to self-report,” Lukkahatai said. “For a nurse, biosignatures can be a guide to develop a tailored nursing intervention and treatment plan that aims to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life.”

Based on current science, Lukkahatai said, researchers are seeing trends that biologic, psychological, lifestyle, and environmental factors may affect symptoms, such as:

- Disruptions in the gut microbiome linked to increased risk of chemotherapy-induced nausea

- Drops in inflammatory markers after ear acupressure linked to reduced chemotherapy-induced neuropathy

- Prolonged inflammatory response linked to chronic fatigue and cognitive dysfunction

- Proteins in neuroprotective pathways linked to decreased intensity of symptoms during cancer treatment

- Specific genes linked to an increased risk of sepsis

- Two microRNAs linked to acute graft-versus-host disease

“My dream for oncology nursing is to have biosignatures that allow us to identify high-risk patients across a variety of nurse-sensitive outcomes, including symptoms, functional status, fragility, and quality of life,” Singh said. “These outcomes are extremely important to patients receiving cancer treatment as well as survivors.”

Lukkahatai and Singh recognized that the use of symptom biosignatures in cancer care is still in its infancy. However, researchers have made strides in identifying them, and they have huge potential to benefit patients.

Biosignatures in Clinical Practice

“With the advent of relatively cheap molecular tools, diseaserelated biosignatures are being developed,” Singh said. “Treatment modalities are changing, and research on biosignatures may help manage emerging immune-related adverse events. As more nurse scientists learn about molecular mechanisms, we will develop more biosignatures for more symptoms.”

Lukkahatai and Singh said that some of the barriers at the bedside include cost and knowledge gaps. Collecting and measuring biosignatures require precision, accuracy, and time to analyze and interpret the data. Most biosignatures rely on information from one or more molecular test, Singh said. Lukkahatai added that the timing of testing and even just how the patient feels during the test can alter results.

“In oncology, multiple tools like self-reporting, clinicianadministered tests, and physiologic measures are part of our clinical practice,” Lukkahatai said. “With the complexity of cancer symptoms and treatment regimens, completing all of those elements can be burdensome to both patients and nurses.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a spectrum of biosignature-based genetic and genomic tests to predict both response to treatment and risk of disease recurrence, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology and National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend certain tests in their treatment guidelines.

“With any type of risk appraisal tool, nurses need information on the sensitivity and specificity of the biosignature,” Singh said. “If a biosignature is not accurate, then patients run the risk of being under- or overtreated.”

Options and Opportunities

As the implications of biosignatures in all aspects of practice evolve at such a rapid pace, everyone from scientists to clinicians is identifying the next steps along every point of the pipeline from discovery to validation to implementation.

“Although we know more about the potential biologic pathways and signatures than ever before, we need consensus among oncology nurse scientists on what variables to include and how to measure them,” Lukkahatai said. “We also need more feasible, evidence-based, and efficient tools for nurses to use in clinical care.”

And at-home genetic tests, available at the click of a button for the general public, are also confounding care conversations. Patients may ask for help in identifying which genetic test is right for them, or they may bring their findings to nurse clinicians to help them understand what the results mean for current and future care—for themselves and even extended family members.

This is where interprofessional collaboration is crucial, Lukkahatai said. Clinicians should seek recommendations of reliable information from genomics experts in the specific areas of concern and educate patients on what to look for.

“We can also select the tests based on their performance and reliability using evidence from previously published articles and performance reports,” Lukkahatai said.

Research Is Evolving

Biosignatures, particularly regarding symptom science, is a new area of scientific inquiry, Singh recognized. Initial efforts focused on evaluating associations between single symptoms and various biosignatures, such as candidate genes and changes in gene expression and gut microbiome profiles.

“Currently, symptom science is moving toward a biosignature approach to generate targeted interventions for symptom management,” Singh said. “The goal of that research is to identify patients at high risk for both single symptoms and clusters, which would help us establish predictive models that oncology nurses could use to provide preemptive patient interventions.”

However, nurse scientists must grow the body of evidence for causes and interventions for symptom clusters for that to happen. Presenters at the ONS BridgeTM conference in September 2020 discussed best practices for conducting symptom science research and recommended that the next steps for oncology nurse scientists is to develop consensus on how variables are measured and how data are collected and analyzed.

With that in mind, Singh is hopeful for the future of oncology symptom science.

“Using new analytics tools like latent variable modeling, machine learning, network analysis, and biosignatures, we are starting to unravel some of these mysteries and develop new treatments to decrease symptom burden for patients and survivors,” Singh said. “I’m so intrigued that significant differences exist in individual cancer symptom experiences. Although some patients report very few symptoms, other patients with that same cancer diagnosis undergoing the same treatment can report 25 or more symptoms from a list of 38. A better understanding of biosignatures would help us improve patients’ quality of life and even advance treatment outcomes.”

How Nurses Can Use Biosignatures in Cancer Care

To better understand symptom science, Lukkahatai encouraged oncology nurses to attend conferences and webinars, form interprofessional journal clubs, and listen to and learn from patients about how they feel and what they do to manage their symptoms.

“What works well for one person may not be the same for another,” she said. “Tailored nursing interventions based on the needs of our patients are key.”

To aid complex clinical decision-making, Singh recommended evidence-based guidelines through credible organizations like ONS and the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. She said nurses should also review recent literature on biosignatures such as these:

- A Novel Biosignature Identifies Ductal Carcinoma in Situ Patients With a Poor Biologic Subtype With an Unacceptably High Rate of Local Recurrence After Breast Conserving Surgery and Radiotherapy

- A Novel Biosignature to Assess Residual Risk in DCIS Patients After Standard Treatment

So much is evolving in oncology symptom science, but as clinicians and nurse researchers use the evidence to optimize patient care, one certainty remains: biosignatures are promising.

“Symptom biosignatures are likely the future for symptom management,” Singh said. “Bringing biosignature research to the bedside will empower oncology nurses to improve symptom management for their patients.”

“As oncology nurses, it is our principle to use a holistic approach when caring for our patients. While we still so have much to learn about biosignatures, symptom-related factors are crucial to providing the best care possible,” Lukkahatai said. “When we consider biosignatures as a combination of self-reported symptoms, environmental factors, biomarkers, and other physiologic measures that can be used to characterize symptoms experiences, then, yes, it is the future of oncology nursing care.”